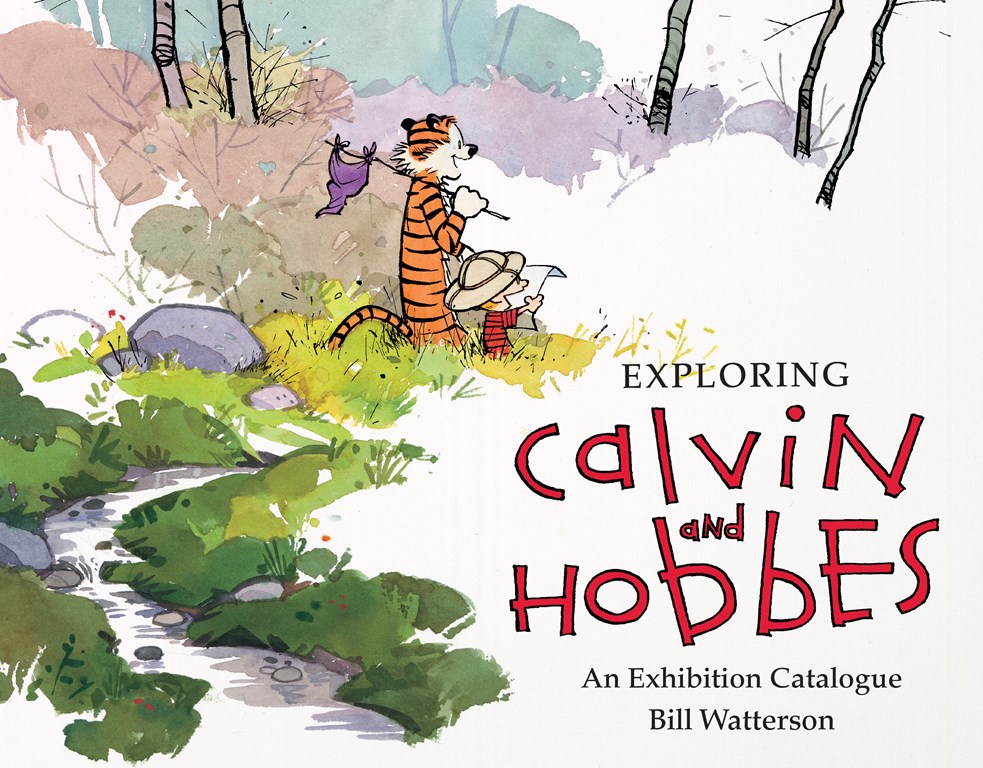

Exploring Calvin and Hobbes

When the latest Calvin and Hobbes book appeared on my front porch, there is little chance the postman recognized he was delivering a piece of my childhood in a hand addressed manila envelope. That is, however, exactly what happened.

For those of you who don’t know, Calvin and Hobbes, is an American cultural landmark. It is a comic strip that ran from 1985 until 1995 in papers across the country and around the world. Unlike many current comics, Calvin and Hobbes was always humorous and often side-splittingly hilarious.

Some comics currently in print have continued for decades, often recycling jokes, offering overly complicated plots with a multitude of extraneous characters, and losing the crispness and energy that once made them great. Thankfully Bill Watterson, the man behind Calvin and Hobbes, knew when to walk away and stopped drawing the strip after a decade.

Bill Watterson is a somewhat enigmatic artist. He did very few extended interviews while the strip was in print. Since he retired from drawing Calvin and Hobbes he has largely been out of public view. Many creative people are ready to write an autobiography to cash in on their celebrity as soon as they’ve had success, often providing tedious details of their creative processes. Watterson, on the other hand, has left his many fans largely in the dark.

Exploring Calvin and Hobbes

This new book from Andrews McMeel Publishing is a breakthrough for the hungry Calvin and Hobbes fan. Exploring Calvin and Hobbes: An Exhibition Catalogue begins with an extended interview with the man who curated a recent exhibit of Calvin and Hobbes strips at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. In this interview, Watterson discusses his childhood, how he became interested in cartooning, his various attempts to break into the industry, and how the production of Calvin and Hobbes took place for its decade-long run.

The second section contains ink on paper samples of some of the cartoonists and illustrators that influenced Watterson. These samples were chosen and annotated by Watterson himself. Next, there are samples of Watterson’s early efforts at editorial cartooning and submissions to syndicates that never made it to press. Finally, the collection includes many pages of samples of published cartoons from the strip’s epic run. These are original, ink on paper drawings that sometimes have whiteout, pencil marks, and even scotch tape visible. The final portion of the collections was selected by Jenny Robb, who is an associate professor at Ohio State University and a curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. They reflect her choice of some of the best and most representative strips that Watterson created.

Conclusion

To say that this book is a delight is an understatement. The pages are visually appealing, the layout creative, and the arrangement of the material tells the story well. The interview is engaging and highlights some of the information any true fan of Calvin and Hobbes should want to know. This is a pearl of great price.

Exploring Calvin and Hobbes is not the best entry point for people new to the strip. Starting here would be like trying to read the appendices to The Lord of the Rings before reading the book itself. Every true fan will read the appendices, but only after they have carefully digested the main body of work. The same applies for Watterson’s oeuvre.

However, for those that have read most or all of the Calvin and Hobbes cartoons, especially those who remember poring over the graphic delights offered by the strip during its newspaper run, this is a true gift. It is worth the time and well worth the money if you have the good fortune to be able to buy this volume.

You can see the daily strips and subscribe to have them in your social media account through the GoComics web distributor: Click Here.

Note: A gratis copy of this volume was received from the publisher with no expectation of a positive review.