The Wisdom Pyramid - A Review

We don’t hear as much about wisdom these days in modern discourse.

We hear about expertise, eloquence, and clarity.

None of those three things are bad things in and of themselves, but they are a far cry from wisdom.

Any good Bible reader can tell you that wisdom is a good thing. Wisdom is personified by Solomon in the Proverbs. Moreover, James urges his readers, “If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask God, who gives generously to all without reproach, and it will be given to him.” (1:5) The alternative to wisdom is being a doubter who is “like a wave of the sea that is driven and tossed by the wind.” (1:6)

To be honest, being tossed like a wave seems to be the standard state of most people in our culture. People tend to have a ton of information at their fingertips, especially since most of us carry the internet in our pockets. But having information without knowing what to do with it leads to being wind tossed. Having a framework that allows us to do something with available information is a step along the way to wisdom. True wisdom is having a true framework that can handle all available data.

Brett McCracken’s book, The Wisdom Pyramid, published in 2021, is a helpful, popular level book on the problem of information overload (or wisdom deficit) with some practical solutions. It’s more than a jeremiad and much more than a self-help book.

McCracken identifies the problem of information overload, with statistics that help illustrate the immense increase in volume and range of information we are exposed to. He also notes there is a constant pursuit of novelty in our world—there is always something different coming down the pike. This is complicated by the emphasis on finding meaning within, so that one’s moral compass is guided by one’s current feelings.

This sort of condition helps explain why many of feel ill at ease in the world. There is no solid ground. We have not been taught how to navigate this world. We are often overwhelmed by the battering of the wind, like waves of the sea. Too seldom have we asked God for wisdom.

As part of the solution, McCracken proposes a six-tiered approach to information intake. Much like the food pyramid paradigm that used to guide our nutritional sources, the foundation layer is the most plentiful with the top level being consumed sparingly.

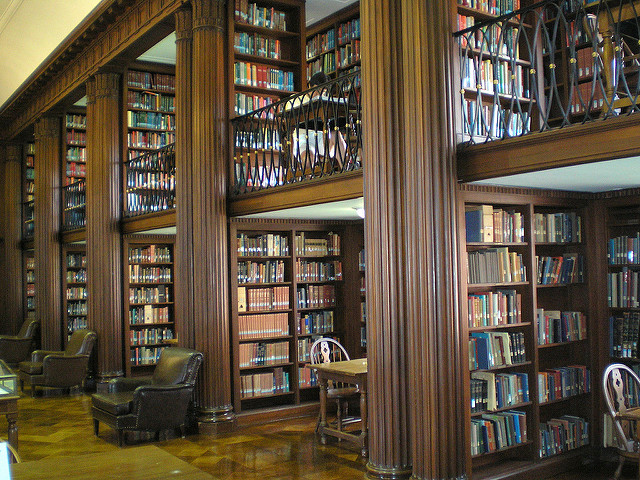

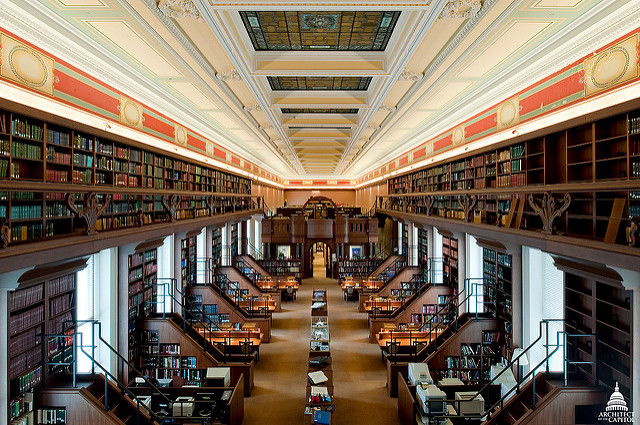

It is little surprise that McCracken, a regular contributor to The Gospel Coalition, begins with Scripture intake. The Bible should make up the largest volume of our information diet. The Word of God is food for the soul and we should feast on it regularly. After that the teaching ministry and community of our local churches should be a plentiful source of content. In a reasonably healthy church with other believers also trying to consume great volumes of Scripture, that fellowship and teaching should echo the foundation of the pyramid.

McCracken recommends that nature form the third tier of the ever-narrowing pyramid. It has certainly not helped our culture’s understanding of truth to believe we have conquered the outside and that we can master nature. The heaven’s declare God’s handiwork, if we’ll only take time to listen. The next level in the wisdom pyramid is books. Old books are good, because they help us see the problems with our own age. New books can be good because good books explore topics with a depth and precision that blogs, newspaper articles, and social media does not.

The penultimate layer of the wisdom pyramid is exposure to beauty. McCracken recognizes the transcendent nature of beauty—that it isn’t merely a human appreciation, but reflects the order of the universe. More significantly, he knows that because has emotive power that comes and goes. It cannot be the main pursuit, though it can point us toward the other transcendentals: truth and goodness. Finally, at the tippy top of the pyramid is the internet and social media. These are the “fats, oils, and sweets” foods of the old food pyramid. Great treats, but terrible for long-term health when taken in large quantities.

The wisdom pyramid is helpful. It may not perfectly reflect the opportunities we have, but it should be something we aspire to replicate. Our problem is that most of us have reversed the pyramid. We live online and dabble in the others. It’s a good thought to try to wean ourselves off our phones and the internet (except my blog, of course), and spend more time at the bottom of the pyramid.

After all, we should be seeking wisdom. And wisdom is best found in the words of the author of the universe. Indeed, where else shall we go, for Christ has the words of eternal life? (John 6:68)

Reading your Bible is a battle. There’s a reason why Paul lists Scripture as the sword of the Spirit in his discussion of the armor of God (Eph. 6:17). More even than that, Scripture reveals God’s character and is, thus, central to worshiping well (Psalm 119). That’s why reading the Bible is a battle.