A Look at One Case for Population Control

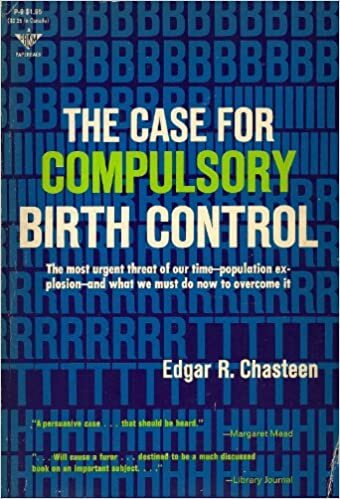

In the deep, dark corners of the Southern Baptist Convention’s theological past is a sociologist who taught at a Missouri State Convention affiliated college, wrote for the Christian Life Commission (the precursor to the ERLC), and advocated for abortion, forced sterilization, and legal penalties for exceeding an approved number of children. Since that point, his college disassociated from their denomination and Chasteen went on to form a non-profit organization dedicated to affirming the equal validity of all religions. Just how Baptist or even Christian Chasteen is or ever was is up for debate. There is little in his 1971 book or his various websites that can connects him to anything like Christian orthodoxy.

The thesis of Chasteen’s book is “that unless we act now to legislate a limit of two children per family, we have little hope of solving the other problems that beset us.” (vii) That problem Chasteen describe as an insidious disease: “The cancer of runaway population growth has eaten away both heart and soul of the body politic. We are on the verge of anarchy with only our will to survive and our determination to act staying our fall.” (33)

For Chasteen, every problem was driven by overpopulation. He writes, “If, as a nation and as individuals, we can summon the intelligence and the courage to bring population growth under control, we will find ourselves still faced with problems of race relations, crime, alienation, apathy, environmental degradation, and so forth, but with one big difference. The problems will then be capable of solution, whereas now they are not.” (33)

Chasteen echoes Paul Ehrlich’s popular book, The Population Bomb, in his concern for the growing number of individuals on the planet. His book, The Case for Compulsory Birth Control, was written while the Rockefeller commission was composing their report, which was commission and subsequently rejected by Nixon. Like Chasteen, the Rockefeller commission affirmed eugenic policies, widespread birth control funded by the government, and the expansion of access to abortion. Unlike Chasteen, the Rockefeller Commission only advocated for voluntary sterilization.

The entire tenor of Chasteen’s book is anti-human. He expresses concerns that “Death rates in the industrializing nations began to drop while birth rates remained at their previously high levels.” (25) Which leads to complaints that Americans shared medical technology with developing nations with a false sense of compassion and without permission.

Argues Chasteen:

“America has shared its medicines with the world, thinking that by doing so it was saving millions of people from early death, and so it was. . . . [However,] we were operating on a foundation of mistaken morality which made keeping people alive and end in itself. We inoculated, immunized and sprayed, and we felt good about our actions. . . . Motivated by benevolent ignorance of social forces and human desires, America played unintentional havoc with the destinies of nations and peoples. . . . In some parts of the world death rates were cut in half in only a decade, and sometimes without the consent or knowledge of the governments affected.” (26–27)

There is more, but it does not get much better.

At the root of Chasteen’s ethics is an individualistic, subjectivistic presumption: “An action is moral only when prompted or hindered by what is right as defined by the individual conscience.” (187)

In light of that naked assertion, Chasteen argues, “What this means is that a new rationale for sexual responsibility and exclusiveness is needed.” (187)

Chasteen demonstrates a full-throated adoption of the sexual revolution:

“Contraceptive technology has made it possible to separate sexual intercourse from conception, making it possible (and necessary) for us to rethink the philosophy of sex worked out before contraception. A very simple formula can be stated:

coitus – contraception = procreation

coitus + contraception = expression” (184)

He celebrates the individualism and autonomy of human sexuality because sex became disassociated from procreation, so that a woman on chemical birth control “can express her sexuality as she expresses her opinion––because of the meaning it has for her as an individual.” (184) He makes a similar argument for males who have had vasectomies.

Chasteen makes clear what contraception has done for sexual ethics in contemporary society:

“Contraception makes it possible to view sex as voluntary, interpersonal behavior rather than a necessary act of survival. Sex becomes a special method of communication between male and female. Sex thus loses its exclusively biological meaning and becomes more social. Like all social relationships, sex can be made constructive or destructive, depending upon the attitude and behavior of those involved. Sex can become a dialogue between two people in which comes to understand and appreciate the other. It can be an expression of the mutual dependence to human existence. Sex can be an enriching and compassionate human encounter or simply another opportunity for exploitation, satisfying a biological urge but destroying humanity socially and spiritually. It’s up to us.” (189)

There are a lot of strands to unwind in Chasteen’s writing on the subject, but he makes explicit the arguments that are assumed in our culture regarding the purpose of sex. The autonomous self is the champion of Chasteen’s moral vision, with no reference to the Christian faith, historical or otherwise. It is the individual alone who determines what is right. (A belief that undermines Chasteen’s plea that his perspective is the correct one, but whatever.)

Several lessons can be gleaned from reading books like Chasteen’s, The Case for Compulsory Birth Control.

1. There were good reasons for the Conservative Resurgence in the Southern Baptist Convention. Chasteen advocates for multiple anti-Christian positions that are untenable with anyone remotely committed with the content of Scripture. The convention had to rid itself of the cancer of those like Chasteen to survive as a gospel-focused entity.

2. The population control movement, which is now growing because of concerns over climate change, has its roots in a dark movement that has to find a way to mourn the decrease in suffering due to premature death. It has not, as far as I can tell, found a way to do so, it has simply tended to skip over the assumption that it would be better if the superfluous people didn’t survive past their age of usefulness.

3. Beware people who see one big social problem as the key to all other problems. A big idea like overpopulation, systemic racism, or climate change can be used as a way to blind listeners to the moral evil being proposed on one front for the perceived good result on another. Society is complicated. Solving climate change won’t fix poverty. Eliminating systemic racism won’t reduce our carbon footprint. Limiting population growth will not eliminate crime. It is impossible to attain a good society through persistent evil.

There’s no reason to doubt that Jesus was nailed to the cross. Ultimately, I trust what Scripture says about Jesus’s crucifixion because I also trust what it says about his resurrection. And that’s what we should be celebrating this week.