Charles Williams: The Third Inkling - A Review

Charles Williams stands in literary history among the group of men called the Inklings. Most famously, that group includes J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Often Owen Barfield is mentioned along with them, too. Williams gets discussed but often on the fringes—a much less known person than Lewis or Tolkien. He remains known, in part, because of his association with the other two.

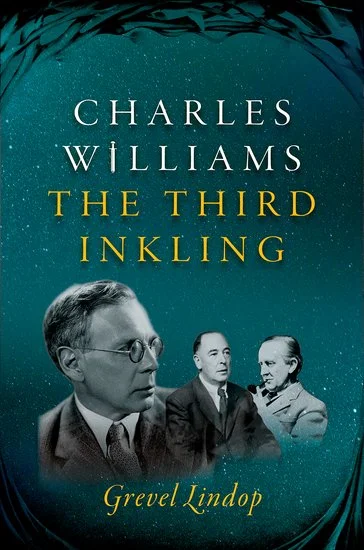

Whereas there are many biographies (authorized and otherwise) on Lewis and Tolkien, there have been few on Williams. Recently Oxford University Press has published a lengthy biography on Williams by poet and literary critic, Grevel Lindop.

Who is Williams?

It is appropriate that OUP publish this biography of the third Inkling because Williams’ biography is as much the history of OUP as it is the story of his own life. He worked for many years as an editor at Amen House, the London office of the Oxford University Press. During World War II, he worked for OUP in Oxford proper.

For the student of English literature, particularly of modern British literature, Williams’ life and work is interesting because of his interactions with the intelligentsia of that era. He corresponded in detail with Dorothy L. Sayers. He was friends with T.S. Eliot. He interacted with Dylan Thomas and Gerard Manly Hopkins and others. Some of these, even more than Tolkien and Lewis, are names that haunt the syllabi in colleges to this day. Williams helped shape the literary history of the English language due to his significant position as an editor of volumes, curator of anthologies, and author of prefaces and introductions. Lindop chronicles the work of Williams quite adeptly along those lines.

Williams was also a creator of literature. He wrote poetry, plays, and novels. Some of them are still in print today. In this endeavor Williams was, perhaps, no less avid than some of his more popular friends. However, he was much less successful.

Although he wrote numerous novels, plays, and poems, he was regularly in financial difficulty. (This stemmed in part due to the low wages paid by OUP.) Yet he, like many other creative people, was frantic to put his vibrant imaginations onto paper and thus bring others into the worlds he was creating. He often published without pay and when he was paid, it was often very little. In that regard little has changed in the literary world.

He was enthralled with the Arthurian legends as well as with mystic and sometimes occult practices. Williams was involved in several secret organizations that incorporated various magical rituals, mystical concepts such as sharing the pain of others, and syncretistic practices that melded Christianity with pagan rites. Most of what Lindop describes is rather benign and not dark magic, as it were, but Williams had shaky theology to say the least.

His Theology and Praxis

Williams was obsessed with his notion of Romantic Theology and wrote a book by that title. The concept is that through romantic love one could have a spiritual experience. Lindop deals with this in some detail, but it is not a fully orthodox conception of worship. However, it points toward some of the disturbing aspects of Williams’ amorous life.

He married a woman for whom he experienced something akin to love at first sight. He and his wife, whom he nicknamed Michal after David’s wife, remained married until his death just before the end of World War II. However, Williams was not faithful to her in any true sense of the word.

According to Lindop, it does not appear that Williams committed physical adultery with any woman. However, he committed many emotional affairs with young women around the office of Oxford University Press. In these relationships Williams often released sexual energy through mildly sadomasochistic practices like light spanking, striking palms with rulers, and other minor forms of “discipline.” Often these encounters occurred in broad daylight in the offices of OUP. In many of these interactions, Williams acted as a spiritual mentor to the young ladies, thus inculcating their devotion and submission to his odd practices.

Williams also developed the idea that the biblical mandate to “bear one another’s burdens” included the ability to suffer by proxy for an individual—to take on the physical and emotional pain of someone, whether known or not, and thus reduce it. He was quite active in organizing these activities among what seems to be a fairly broad group of spiritual followers.

Relative Obscurity

The unwholesome affections and spiritualism help explain why Williams, even when he is read, does not resonate with as wide an audience as Lewis and Tolkien. Certainly, as Lindop documents, Williams was as innovative as the two more famous Inklings, perhaps even more innovative. But his gospel was tainted by spiritualism and distorted understanding of love. This cannot help but come through in his writing. While Lewis and Tolkien are telling the greatest story ever through their myths, Williams was caught up in spiritualism that effectively drew his mind from the truth.

Also, where Lewis and Tolkien understand joy and hope, Williams led an unhappy and unfulfilled life. He was constantly nervous. He was always something of a social oddity. He withdrew from his family often to be creative and productive. Lindop paints the portrait of one who well knew suffering, but little knew joy. This, too, seasons his writing and helps explain why he continues to be read but rarely devoured by generations of devotees, like those that follow Lewis and Tolkien.

Lindop’s biography of Charles Williams is good. The research is well done, with many footnotes and ample evidence of thorough research into Williams’ extensive correspondence and his voluminous literary estate. This is a book that needed to be written and has been written well. If it fails to inspire as much as a biography of another Inkling, that is likely because a fair telling of the life of Charles Williams cannot be a happy story if it is to be an honest one.

Note: I received a gratis copy of this volume from the publisher with no expectation of a positive review.

Reading your Bible is a battle. There’s a reason why Paul lists Scripture as the sword of the Spirit in his discussion of the armor of God (Eph. 6:17). More even than that, Scripture reveals God’s character and is, thus, central to worshiping well (Psalm 119). That’s why reading the Bible is a battle.