Some Thoughts on Scripture, Theology, and Climate

It doesn’t matter if the issue is economics, the environment, human sexuality, or liturgy, when we ask what the Bible says about a topic we need to asking the question of the Bible. We should not try to construct our preconceived notions out of biblical material.

For some, this is an obvious statement, but as I read theology texts and Christianesque articles on various issues from all angles, I consistently get frustrated with the authors’ well-meaning attempts at eisegesis. It is especially frustrating to someone, like me, who views Scripture as the final norm in all matters of life and faith to fight through an attempt to contort the text to fit their perspective.

Theology and Climate Change

One recent example is a book on Systematic Theology and climate change. Recognizing that climate change is a big deal, and that I expect Pope Francis to affirm anthropogenic climate change in his forthcoming encyclical, I am still puzzling over the approach of this book.

Scripture affirms an earth-positive ethics. That is, an environmental ethics can be built that has strong support from Scripture. What Scripture doesn’t help us with is the particulars about the data that relates to climate change or what to do about it.

This is something we are going to have to watch for in the near future, as the forthcoming papal encyclical encourages growing concern for the environment. We need to be more concerned with the environment than we are. However, we also need to balance our method of response to environmental concerns so that we do not ignore our responsibility to care for the poor, advance medical technologies, and advocate for the life of the unborn.

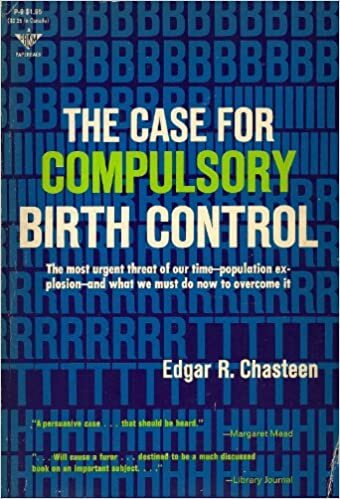

In other words, not everything that comes under the mantle of environmentalism can be matched up with Christianity. This is true despite the fact that we can develop a thoroughgoing environmental ethics from Scripture.

More particularly, we cannot blindly jump onto a policy bandwagon when issues like climate change come into play, even if they are entirely human caused. There are elements in the platform of many climate policy advocacy groups that don’t match a Christian worldview. We need to navigate these waters very carefully.

Challenges for Contemporary Theologians

This is what makes trying to derive a theology of climate change from Scripture. The Bible doesn’t actually say anything about the specific nature of climate change. Therefore, any theology that deals specifically with climate change will have several layers of interpretation between the text and the theology.

There is nothing wrong with applying a biblical worldview to contemporary issues. In fact, I am an avid proponent of this. However, we must do so with care so that the issue does not overshadow the text. In other words, we cannot backfit a theological paradigm to our sense of justice.

Backfitting is exactly what some theologians are doing when they construct their paradigms. They build the foundation under the existing problem.

The answer to the problem, though, isn’t to stop talking about the problem. It’s to come at it the other direction. Scripture is sufficient for every question about doctrine and life. This doesn’t mean that there is a verse in Scripture to answer every question someone can ask. We shouldn’t try to make the Bible be any more exact than it is.

Instead, this means that Scripture has the information we need to construct a worldview that will allow us to receive and apply truth that comes from the world around us. God created the world in an orderly fashion, thus all truth is God’s truth.

The main idea, then, is that we need to be cautious when we claim something as a Christian position. If we do, then it really ought to be built on a carefully formulated framework derived from Scripture. After all, that is the revelation God gave us and by which we claim to judge all ideas.

Photo credit: Bible, by Adam Dimmick. Used by permission. http://ow.ly/OqNhh